Images

Kate Dorney, Joanna Hofer-Robinson, Mia Hull, Cason Murphy, Daniel A. Novak and Carolyn Williams consider the significance of makeup, photography and tableaux in the plays’ representation of race.- The Photograph in The Octoroon and An Octoroon — Kate Dorney

- Hyperfunctional Tableaux in An/The Octoroon — Joanna Hofer-Robinson

- On Makeup — Mia Hull

- What’s Black(face), White(face), and Red(face) All Over? — Cason Murphy

- Real and Imaginary Photography in The Octoroon and An Octoroon — Daniel A. Novak

- Critique of the Melodramatic Tableau in An Octoroon — Carolyn Williams

The Photograph in The Octoroon and An Octoroon

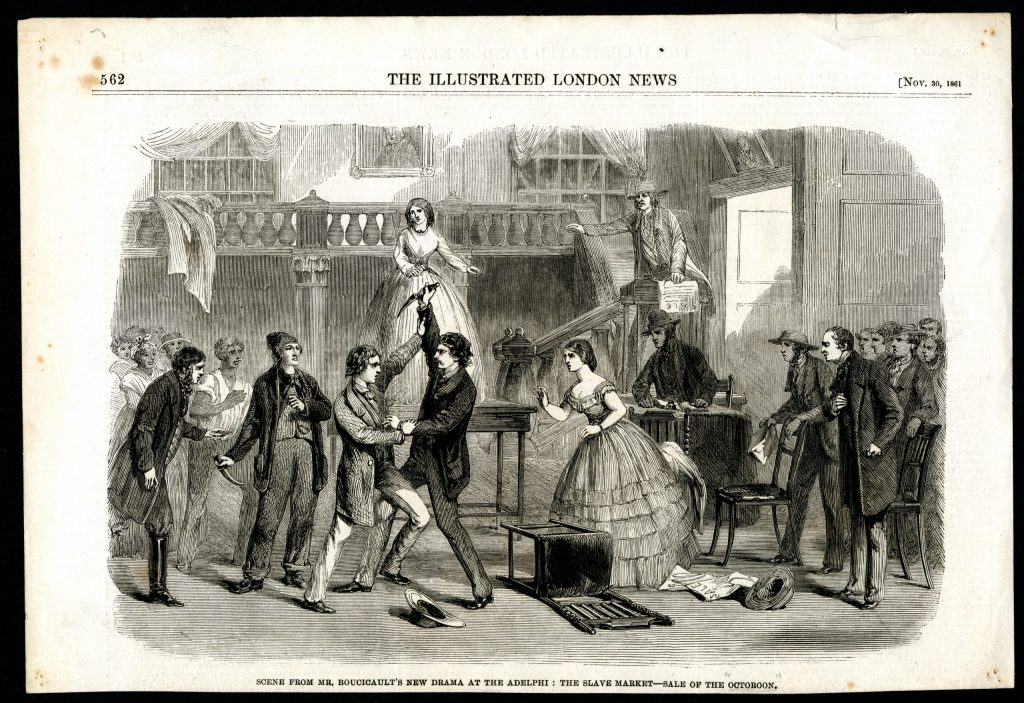

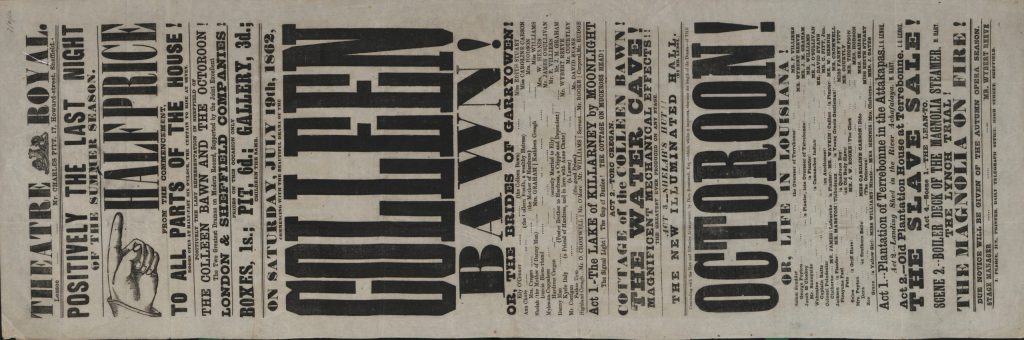

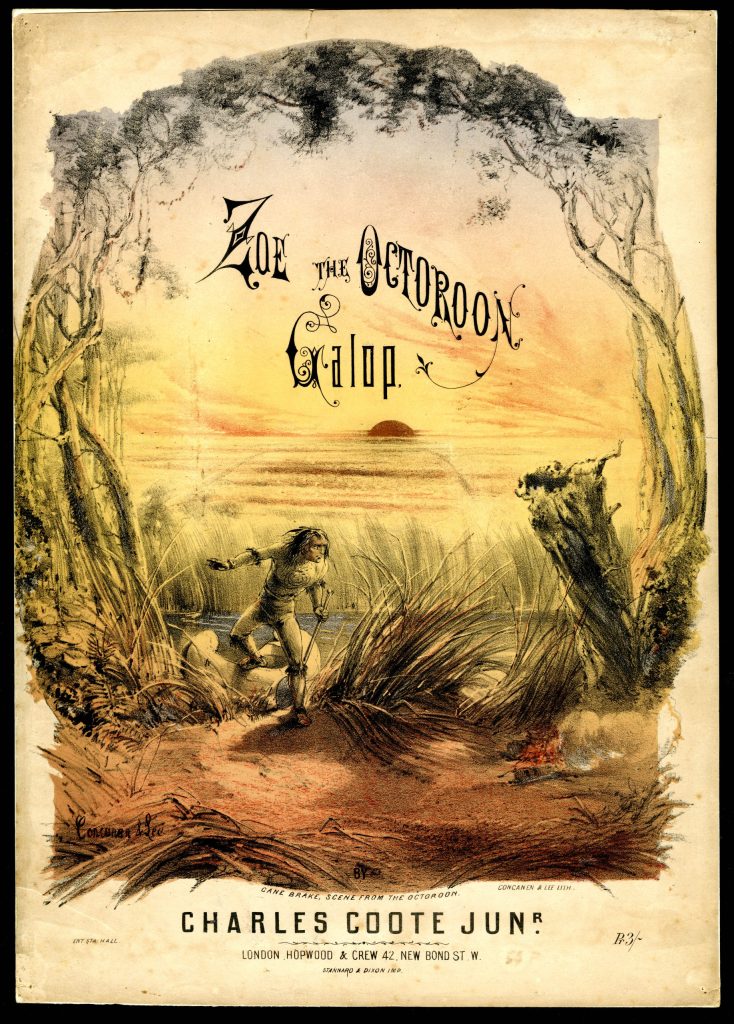

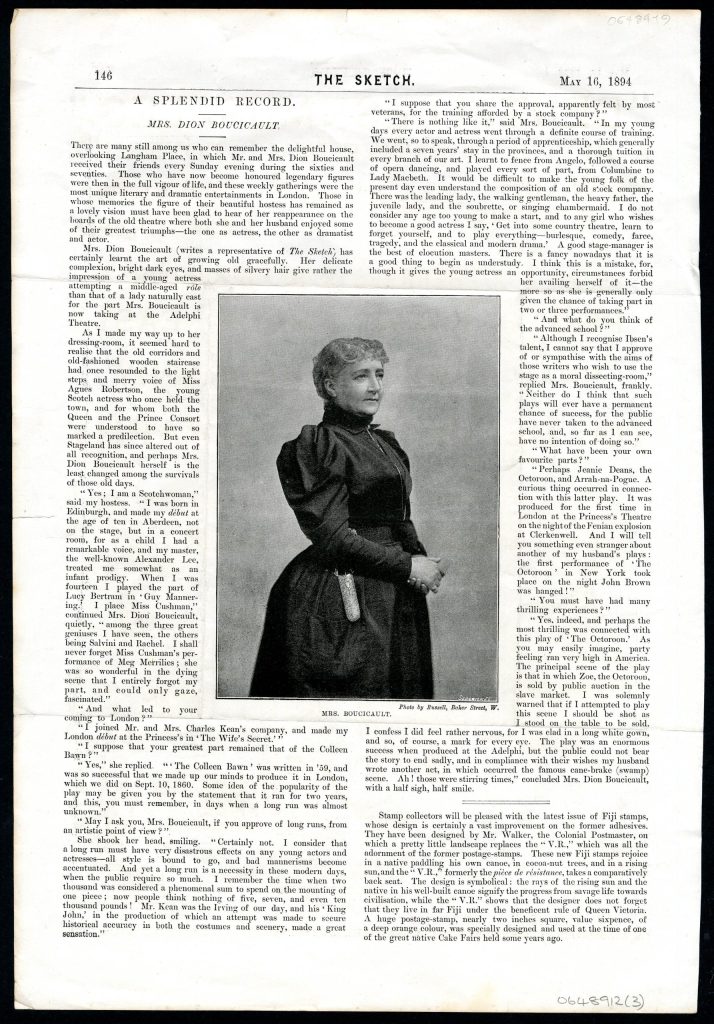

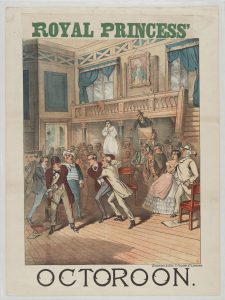

Kate Dorney I want to consider here the interrelationship of sensation, evidence and spectacle as a form of new documentary evidence in Dion Boucicault’s The Octoroon, (1859) and then as an evidentiary spectacle that confronts the audience with the fact of lynching and its afterlife in artefacts in Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ meta-melodrama An Octoroon, (2014).1 The singular act of fictional, furtive white on black violence from Boucicault’s play is substituted for evidence of collective, widespread, public and state-sanctioned white-on-black violence in Jacobs-Jenkins’. Joseph Roach describes The Octoroon as a ‘mortgage melodrama’ in which ‘the “tragic octoroon variant” substituted expendable female bodies for the foreclosed properties of the melodramatic master narrative.’2 The term ‘mortgage melodrama’ usefully conveys the ways in which concealed and revealed documents and attendant concerns about ownership, identity, property and wealth underpin melodrama’s dramaturgical form and logic. The Octoroon features a variety of document types, some standard melodramatic fare (wills, letters, mortgages) and some specific to plantation life such as Zoe’s free papers; the bills advertising the sale of the plantation; and the auction list with the values apportioned to each enslaved person. But the photograph, a new form of evidence, has a distinct dramatic and affective function in these plays. In The Octoroon the photograph accidentally, but providentially, records M’Closky’s murder of Paul and its discovery provides Scudder with the heavenly authority he needs to save Wahnotee from the lynch-mob: ‘The apparatus can’t lie. Look there, jurymen. (Shows plate to the jury.) Look there. Oh, you wanted evidence, you called for proof – Heaven has answered and convicted you.’3 In the new technology of the photograph Boucicault, whom David Mayer described as ‘obsessed with modernity and current technology’, finds a form of document that can perform the same function as the tableaux (another key component of 19th century melodrama) but can also exceed its because of its enduring nature.4 It won’t dissolve like a tableau does and it is, with care, reproducible and will reliably show the same thing every time.5 The photograph’s role in the play is two-fold: for the audience, it is a cue to recall the murder they witnessed at the end of Act Two. For the ‘jury’ (as Scudder addresses them) or lynch-mob (as Boucicault constructs them) it is evidence that M’Closky was the person who murdered Paul with Wahnotee’s tomahawk. More than a century later, Roland Barthes also avowed the power of photography to show truth in Camera Lucida, distinguishing the essence that separates a photograph from other forms of media as ‘noeme.’ Contemplating Richard Avedon’s photograph ‘William Casby, born in slavery, Algiers, Louisiana, March 24 1963’, he noted:the noeme here is intense; for the man I see here has been a slave: he certifies that slavery has existed, not so far from us; and he certifies this not by historical testimony but by a new, somehow experiential order of proof.6Here, as, in The Octoroon, the photograph provides the certainty that the event took place.7 It is the experiential order of proof that moves Barthes, which makes him ‘feel something’ and this, in Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ view, is the purpose of melodrama. The Octoroon achieved affect through the combination of music, plot and sensation scenes in which the jeopardy reaches an unbearable point of tension (the slave auction, the revelation of M’Closky’s guilt and the fire on the cotton steamer). In An Octoroon it is the production of the photograph that is the most affective of sensation scenes, not because justice is about to be done, but because it isn’t. Act Four begins with the characters ‘BJJ’ and the ‘Playwright’ explaining the dramatic purpose of the sensation scene: ‘part of the thrill, part of the Sensation of the scene, was giving people back then a sense of having witnessed something new and novel.’8 The theatre, he continues, ‘is no longer a place of novelty’, it’s impossible to provide an audience with a new sensation, the sensation of ‘finality.’ He can’t stage a real death, sacrifice an animal on stage or set fire to the theatre so ‘I figured I’d try something. I hope it isn’t too disappointing’:

ASSISTANT has wheeled out an overhead projector. He projects a lynching photograph onto the back wall. They perform the following in the light of the projection.9‘The following’ is an absurd dialogue between George defending Wahnotee and deploring ‘lynch law’ as ‘a wild and lawless proceeding’ and M’Closky demanding evidence of innocence. The absurdity comes from the fact that both characters are played by the same Black actor in white face wearing a suit that is white on one side and black on the other. When he speaks George’s lines the white side faces the audience, when he speaks M’Closky’s lines the audience is presented with the black side. The sensation is produced by confronting us not with something new, but with something old. A lynching photograph. This photograph is not an accidental result of God’s justice but a souvenir taken by Lawrence Beitler for the express purpose of recirculation to affirm white supremacy and celebrate and legitimise violence against Black people. In the National Theatre production directed by Ned Bennett in 2018, it was projected not onto a wall but onto a sheet that swayed gently in the breeze created by the performers. The photograph was of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith taken on 7 August 1930. They hang from trees while an animated audience mills around them as if at a fun fair. A figure in the foreground looks into the camera and points at the lynched men. One framed print of this photograph is captioned on the back as ”Bo” point to his n*****.’10 The print is one of the thousands reputedly sold by Beitler.11 Immediately before the projection scene BJJ has described the shaky evidential status of the photograph in the twenty-first century because it is prone to endless forms of manipulation, however, we are not confronted with a faked photograph but an object which, pace Barthes, certifies that this event happened. An object whose status has shifted from the category of souvenir to that of historical artefact indicting lynching. As the projector illuminates the scene, it also illuminates a practice that continued, with the state’s knowledge and without sanction, for a century and more after The Octoroon’s premiere. Scudder has not held this lynch-mob at bay with a discussion of justice and law, the photograph can only show what Saidiya Hartman refers to as ‘the spectacular nature of black suffering and, conversely, the dissimulation of suffering through spectacle.’12 The ending of Scene Four of An Octoroon seems to confirm this as Wahnotee (played by a white actor in red face), repeatedly stabs M’Closky (played by a Black actor in white face), ties a rope around his neck and drags him offstage. Another Black body about to be killed by a white man in front of an audience. Sensation. Kate Dorney is Senior Lecturer in Theatre & Performance at the University of Manchester. Her research is concerned with the material culture of theatre and performance (historical and contemporary), the institutions and structures that enable and constrain it and the people that commission, make, watch and write about it. Her publications include Stage Women 1900-1950: Female Theatre Workers and Professional Practice (edited with Maggie B. Gale) Played in Britain: Modern Theatre in 100 Plays (with Frances Gray), The Changing Language of Modern English Drama 1945-2005, ‘A Black Theatre History of English Theatre in the 1950s’ and a forthcoming monograph on Winsome Pinnock.

Back to top

Hyperfunctional Tableaux in An/The Octoroon

Joanna Hofer-Robinson Tableaux are a characteristic pictorial effect of nineteenth-century stage melodrama: ‘where the actors strike an expressive stance in a legible symbolic configuration that crystallizes a stage of the narrative as a situation, or summarizes and punctuates it.’13 Often formed at moments of high tension, or at the conclusion of an Act, they freeze the action to allow reflection and revelation: consolidating the relational or emotional dynamics on stage; prompting affective responses from the audience; or introducing further cultural referents through stage effects, such as the ‘realization’ of famous images. Tableaux are thus as much a part of the drama as a break in the action. They foreground the inner workings of the play, but they also have the potential to introduce meanings beyond those directly articulated, or to transform them entirely. This is true of Dion Boucicault’s 1859 sensation melodrama The Octoroon, which – particularly in its original American production – used a tableau to offer dramatic resolution additional to the playscript; for instance, by confirming that Wahnotee revenges himself for Paul’s death by murdering M’Closky.14 However, this play also turns the typical stasis of tableaux on its head. Boucicault constructs a situation in which arrest is action, rather than a check on its forward momentum, by making a tableau – captured as a photograph – the key device through which Paul’s murder is solved. The link between crafting a dramatic ‘picture’ and posing for the camera is made explicit in the play. ‘Here you are, in the very attitude of your crime!’15 Daniel Novak has read this staging of photography in The Octoroon as a metatheatrical commentary on the ‘strange temporality of the tableau’16– which is both frozen image and kinetic performance – as well as on the stop-start rhythms of melodrama, its ‘waves’ of emotional intensity and relief.17True. Nevertheless, the audience rather slides out of view in this interpretation. I suggest that Boucicault’s inversion of the tableau can also be read as an inversion of the subject-object relation through which nineteenth-century pictorial dramaturgy has been previously understood. In the burgeoning field of infrastructural humanities, it is a cliché to state that infrastructure remains invisible until it ceases to function as infrastructure. Despite their frequently enormous scale, infrastructures such as roads, railways, shipping, and warehouses typically become the taken-for-granted background of everyday life, so long as they facilitate the frictionless circulation and exchange of people, goods, and capital. Infrastructural breakdown, by contrast, brings these hitherto unnoticed processes of mobility and connection to light. Infrastructural failures have thereby received a disproportionate degree of attention in critical studies, because their disruption of mundane sites and processes seems to promise to reveal the obscure apparatuses through which political rationalities are solidified in material form, and then translated into collective structures of feeling.18But, as John Seberger and Geoffrey Bowker argue, a focus on infrastructural failure narrows scholarly engagement onto specific artefacts, highlighted in their moment of stoppage, rather than those interrelations that result from their proper functioning. Moreover, it flattens our understanding of the range of possible subjectivities and modes of engagement that develop in relation to infrastructure.When infrastructure becomes visible through breakdown, its visibility, whether described through the eyes of its frustrated users or not, is always already an objectival visibility. The condition of visibility emerges as a result of a condition of the object: its brokenness. Thus, to speak of infrastructural breakdown’s impact on subjective users is necessarily to frame the experience of infrastructure in an objectival lens: one sees the user framed by their objects; one does not see objects framed by their users.19Seberger and Bowker propose that we can reorient our perspective by attending to moments of infrastructural ‘hyperfunctionality’: ‘instances in which infrastructures become visible through qualities of their functionality, but in becoming visible, bring about the experience of absurd alienation on the part of their users: where the world of the user appears off-kilter and the human subject stands as separate and separable from the infrastructures that subtend their daily lives.’20 For example, when the appearance of personalized advertisements for unwanted products on a smartphone prompts the user to reconsider their identity and worldview in relation to their encounter with a mundane infrastructure, which they have experienced as newly unsettling. If we apply this thinking to nineteenth-century dramaturgy, we can recognize that an objectival view of the audience is promoted by accounts of stage tableaux that foreground their complex imbrication with the broader visual culture of the period, their proto-cinematic qualities, or their dramatic effects. Individual subjectivity is analysed through a particular set of possible reactions, dictated by the objects available (otherwise the suspended constellation of actors and mise en scène). For example, recognition of the famous image realized on stage, or not. In such accounts, the human is seen through the lens of the tableau/object and is therefore ‘a reduction’, as the range of possible reactions and experiences to the artwork is narrowed or closed down.21 By contrast, Boucicault’s inversion of the tableau as action permits us to reconstitute the audience as subjects, because the tableau can be experienced as hyperfunctional. Boucicault foregrounds the tableau’s potential to affect (the audience) and to effect (the drama), and so renders the qualities intrinsic to tableaux newly visible through metatheatrical play. Tableaux present paradoxical situations, in which the highly stylized attitudes of actors are supposed to externalise an inner truth, making authenticity an aesthetic concern and product. In The Octoroon, the introduction of the camera into/as a tableau can induce a sense of absurd alienation because it draws attention to these functional qualities of tableaux in a new way: representational truth and documentary proof are simultaneously a technologically mediated artifice, and the expected relation between stasis and action is upset. Consequently, the inverted tableau made audiences newly visible to themselves by challenging their expectations, and by drawing attention to how their own experiences are mediated by technology – the camera, but also implicitly those other stage technologies, such as lighting, or the special effects that Boucicault developed for his sensation scenes. Thus, the audience were ‘caught between the agency of the object and their own embodied agency.’22 Through this perception-heightening state of alienation, the locus of agency shifts to the audience who – aware that they are witnessing something that ‘is somehow different than expected’ – are forced to reconsider their relation to the action on stage.23 However, as Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ deputy, BJJ, comments in his 2014 adaptation, An Octoroon, in a modern context ‘it’s really hard to describe how this scene works.’24 This, as BJJ muses, is partly the result of historical distance. We are simply too accustomed to the proliferation and instability of photographic images, so it is not strange or alienating when a mediated image is slipped between the audience’s expectations and experiences. Even so, the historical distance also permits An Octoroon to succeed in using the same device to create an effect of absurd alienation that turns the audience back on itself. In lieu of Boucicault’s sensation scene in Act IV, An Octoroon projects a photograph of a lynching. In nineteenth-century theatrical tradition, the picture, which shadows the photographic tableau/reveal discussed by BJJ, disrupts, but also compresses, linear time, bringing the now of the image into contact with the now of the audience. Audiences are asked to reflect and to be self-conscious about their individual reactions to the image. The Orange Tree production made this demand emphatically by staging the play in the round with the photograph projected onto two sides of a screen at an angle; in this way, the audience not only witnessed the image but witnessed, and were witnessed by, other members of the audience as they did so. Thus, the object is experienced from the vantage point of the subject, who constitutes themselves anew in relation to their consciousness that the photograph represents shameful historical realities and their own positionality. Hyperfunctional tableaux thereby enable us to read the pictorial dramaturgy of the nineteenth century stage as an enduringly political form: one that intervenes in contemporary thought by reconstituting subjects anew. Joanna Hofer-Robinson works in the English and Comparative Literary Studies department at the University of Warwick, UK. Her publications include Dickens and Demolition (Edinburgh UP, 2018), Sensation Drama, 1860-1880: An Anthology (co-edited with Beth Palmer; Edinburgh UP, 2019), and The Plays of Charles Dickens (co-edited with Pete Orford; Edinburgh UP, 2025). She is currently writing her second monograph.

Back to top

On Makeup

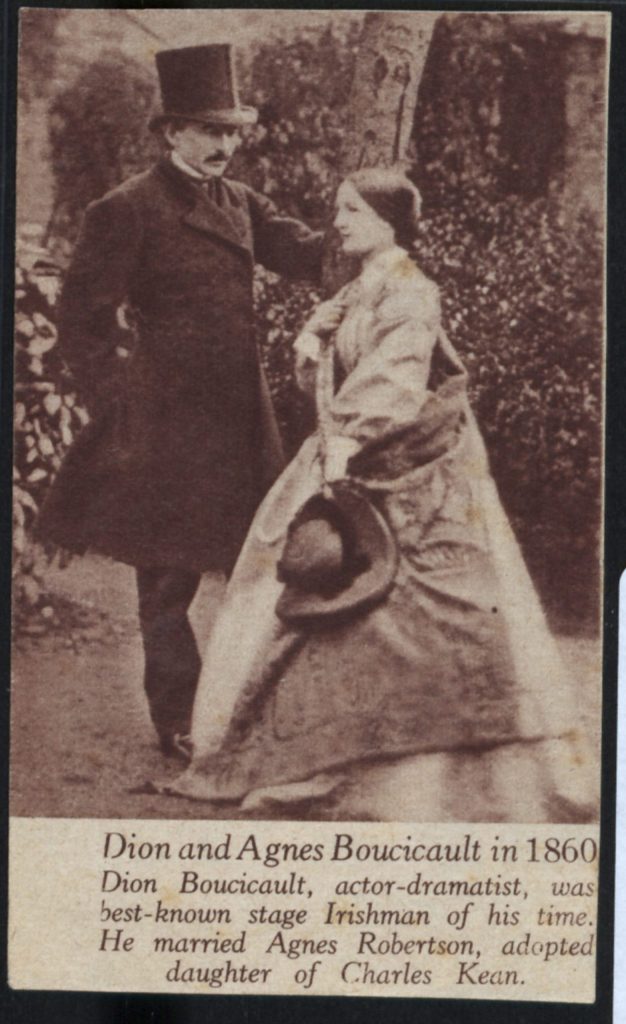

Mia Hull Blackface – the performance convention and racial prosthetic – is a key vector of meaning in both Dion Boucicault’s The Octoroon (1859) and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ An Octoroon (2014). Dave Cockrell provides a somewhat blithe definition of the practice whereby ‘nineteenth century white men put on black makeup and more or less mocked black people though song, dance, and speech.’25 Nevertheless, his seemingly irreverent ‘more or less’ speaks to the insidious ubiquity and quotidian power this form took on. It was so widespread and stratified a convention that even Black performers, such as the acclaimed Bert Williams, would don blackface to portray Black characters well into the twentieth century. The theatrical convention did not just reflect the culture, but was itself a driving apparatus of oppression, instrumental in forging ‘race’ as we know it. To use Ayanna Thompson’s formulation, blackface was the technology through which performing blackness was secured as white property.26 In both Boucicault’s The and Jacobs-Jenkins’ An, what stands out most in their use of blackface is an absence. In The Octoroon, its noticeable lack on the titular character throws into sharp relief the complications of stage representation. Blackface features heavily in the piece: the play opens with what would have been recognisable as a blackface minstrel act, complete with pratfalls and a bit with a banana. On a stage surrounded by white actors portraying enslaved characters in blackface, Zoe, the ‘octoroon’, (who is positioned in the text on the margins of multiple binaries: white/black, enslaved/free) is faced with the ultimate binary of nineteenth and twentieth-century stage representation: to appear in blackface or not. As Zoe was traditionally portrayed by a white actress (famously Boucicault’s wife Agnes Robertson in early productions), the choice to not put Zoe in blackface not only identifies her absolutely with whiteness, by the stage conventions of the day, but also potentially shows a crack in the logic of race narratives themselves. The choice to remain within the terms of the binary – she is not presented in a halfway-blackface or brownface alternative – makes visually explicit the convention’s blatant oversimplification as a technique of dehumanisation. I would hesitate to push the complications of Robertson’s makeup-less representation of blackness too far: even without donning blackface, she stays safely within Thompson’s parameters of ownership. Blackness remains the property of white performance, perhaps even more explicitly. The absence in Jacobs-Jenkins’ An Octoroon comes in the text of the play itself. The word ‘blackface’ is never used, not in the stage directions nor in the dialogue. The text does, however, call for a physical transformation of a non-black actor that leaves little confusion as to the imagery and racial prosthetics that are being evoked. The Assistant ‘prepar[es] his own makeup, wigs, and costumes for Pete/Paul’ (who are the play’s two Black male characters).27 The play’s two other forms of racial prosthetics – ‘redface’ and ‘whiteface’ – are named, rendering the absence of the word blackface both stark and purposeful. Yet, the use of blackface is integral to the play. It functions as one of the adapted materials, alongside The Octoroon itself, in a piece that is as much about adaptation as it is an adaptation. The very tension of representation revealed by its lack of appearance on Zoe in Boucicault’s piece is useful to Jacobs-Jenkins. It underscores the very difficult question of how to represent Blackness onstage, when its performance has historically been the property of whiteness. This difficulty extends not only to visual but also to acoustic representation. As Jacobs-Jenkins writes in his stage directions, ‘I’m just going to say this right now so we can get it over with: I don’t know what a real slave sounded like. And neither do you.’28 The Octoroon actually features as an important entry in the history of whiteface: in 1916, in answer to Harlemites’ complaints about the ‘paucity of Negro dramas’ in their programme, the Lafayette Players in Harlem mounted The Octoroon with an all-black cast and a Black actor ‘whiting up’ to play George.29 For An, the additional involvement of whiteface and redface is essential. The web of male cross-racial casting – cheekily and poignantly represented through ‘make-up’ – does effectively centre the Black actor in the primary roles and the white actor in the sidelined ones. By switching who is on the receiving and dispensing ends of acts of violence, it largely avoids reifying structures of oppressive power onstage. The audience is not forced to watch another Black child be murdered by a white person when M’Closky kills Paul, and a Black actor does not have to embody another violent death. However, the device, entrenched in violence as it is, never truly acts as a reclaiming. Later, when Wahnotee drags M’Closky off with rope round his neck, because of the reversals achieved through the racial prosthetics, a white actor is lynching a black actor. Remaking stage representation is never as simple as painting faces or reckoning with history. More is at stake than undermining the construction of race with Jacobs-Jenkins’ evocation of such a charged and damaging visual device. How Jacobs-Jenkins chooses to update this paragon of sensationalist theatre is crucial. J.K. Curry identifies ‘both the sense of physical spectacle and related bodily response of an audience’ as integral to a ‘sensation scene’.30 Analyses of An draw attention to its use of a lynching photograph as a replacement for The’s burning boat, camera as deus-ex-machina, and slave auction ‘sensation scene.’ However, that photograph is quickly taken down and rejected as the theatrical solution in the script. Daphne Brooks suggests that there is another ‘sensation’ activated by The aside from its flashy gimmicks: ‘Like the ritual of spectacle in spectacular theatre, The Octoroon ultimately exposes “race” […] as an elaborate stunt, a construction of gargantuan and highly spectacular proportions.’31 If race is the exposed element in The Octoroon, blackface/whiteface/redface is the instrument of shock for a contemporary audience. In An, BJJ and Playwright state the impossibility of novelty in the theatre— all that is left is ‘an actual experience of finality’—which makes a contemporary sensation scene difficult.32 But the fusion of physical spectacle and an audience’s visceral reaction comes with this gesture of (non)novelty. The most shocking theatrical technology for a contemporary audience is a practice from the past. Mia Hull is a London-based theatre director, dramaturg, and researcher from NYC. Her research focuses on adaptation, radical cabaret, and contemporary performance as pedagogical apparatus.Back to top

What’s Black(face), White(face), and Red(face) All Over?

Cason Murphy At age 14, playwright-to-be Branden Jacobs-Jenkins saw Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot at the Studio Theatre in Washington, D.C. The 1998 production featured African American actors Thomas W. Jones and Donald Griffin as Vladimir and Estragon, performing in blackface with traces of white makeup. This racialized interpretation of Beckett left Jacobs-Jenkins ‘completely riveted’ as a young Black audience member.33 The experience planted the seeds for his career-long exploration of race, history, and representation in theatre. As an undergraduate in anthropology, Jacobs-Jenkins focused on historical productions of the American stage. When he turned to playwriting, he sought to dissect the ‘historicity of racial representation,’ an endeavor that finds full expression in his play An Octoroon.34 Frequent collaborator Sarah Benson notes, ‘People aren’t sitting around talking about history in his plays…he’s embedding these ideas in the actual form.’35 This embedding is evident in An Octoroon – where Jacobs-Jenkins attempts to reconcile his interest in a racist melodrama from 1859 by specifically using the dated tropes and practices of the theatrical form to critique the notion of race as an ‘optical, illusionistic, phantasmagoric stunt.’36 To do this, An Octoroon directly engages with its 19th-century melodramatic source material, Dion Boucicault’s The Octoroon. Boucicault’s melodrama dramatizes a ‘passing narrative’ centered on Zoë, a light-skinned Black woman raised as white on her father’s plantation, whose liminal identity underscores the instability of racial categorization. Unlike the earliest minstrel shows, in which ‘the ‘blackened-up’ white body became the narrative focal point,’ passing narratives relied on visible elements of black bodies – such as skin pigmentation, hair texture, and facial features – being deemed ‘white enough’ by spectators.37 The original production relied on audiences’ willingness to ‘see’ race through visual cues and textual descriptions, such as Zoë’s ‘bluish tinge under her nails and around her eyes’ – a ‘dark fatal mark’ emblematic of her Blackness (despite Zoë being played by a fully-white actress in performance on the segregated stage).38 Boucicault uses these elements of Zoë’s body to amplify her tragic status, reflecting the antebellum melodrama’s interest in the tension between moral truths and racial hierarchies in society. In An Octoroon, Jacobs-Jenkins’ approach mirrors his experience with Godot: he reimagines an iconic work by embedding critiques of racial representation within its form. Jacobs-Jenkins uses the melodramatic conceit of face makeup not only to echo the theatrical conventions of Boucicault’s era but also to further interrogate the lasting effects of cross-racial performance on the American stage. The play begins with ‘BJJ,’ a metatheatrical stand-in for Jacobs-Jenkins, who applies whiteface while narrating his frustrations as a Black playwright. BJJ’s transformation is both grotesque and absurd, involving loud music, a flask of alcohol, and a deliberately uncomfortable wedgie – a sequence that highlights the performative absurdity of race itself. While essential to the current text of the play, this symbolic opening was actually devised in response to a crisis during the play’s first iteration in 2010. Director Gavin Quinn, an Irish native, left the production a few weeks into rehearsal, followed by all the white actors shortly before previews – in protest over the play’s racial politics.39 Jacobs-Jenkins responded by staging the play through minimalist techniques to highlight the absence of whiteness on the stage. The playwright introduced the play with a lengthy monologue about the incident while applying red makeup before enacting an argument with ‘the director,’ then later performed all the major white characters in whiteface by himself, often playing scenes meant for two characters with only one actor – elements that can be seen in evolved forms in the current version of the play. This decision amplified the play’s exploration of theatrical failure and collaboration, turning an act of necessity into a pointed commentary on the fragility of whiteness in both theatre and society. This experience informed Jacobs-Jenkins’ 2014 revision, where it evolved into a ‘meta-melodrama’ that seamlessly intertwined the 1859 world of The Octoroon with the present day. The use of face makeup in the 2014 production became a tool for further exploring contemporary racial anxieties by simultaneously inhabiting and subverting 19th-century theatrical conventions. For example, BJJ’s portrayal of George, Scudder, and M’Closky – all white characters from Boucicault’s original – underscores the performative absurdity of racial categories while drawing attention to their historical persistence. Curiously, in the original text, these characters were all outsiders to the Southern plantocratic setting. Despite being white, they are perceived in the narrative as possessing varying degrees of ‘Otherness.’ Jacobs-Jenkins amplifies this alienation by having a Black actor embody them. (It is worth noting that in 1916, the all-Black Lafayette Players staged the play with Black actors in whiteface—curiously anticipating Jacobs-Jenkins’ inversion of racial performance by over a decade while further intermingling his play with the history of the original.)40 Jacobs-Jenkins further uses Boucicault’s text as a theatrical palimpsest by complicating the racial depiction of Wahnotee, a Native American character. Wahnotee was originally played by the Boucicault himself in redface, a common practice for 19th-century melodrama. During An Octoroon’s prologue, the character ‘The Playwright’ – a caricature of Boucicault – applies redface while drunkenly mimicking BJJ’s previous behavior, mirroring the power of those theatrical actions while underscoring their temporal and ideological dissonance. The Playwright wears the makeup as Wahnotee during the action of the play, but also during his performance of the white ‘redneck’ character Lafouche. This triangulation of cross-racial performance culminates in the appearance of a Native American assistant to ‘The Playwright’ who dons blackface to portray other stereotypical enslaved Black characters. Historically, blackface, redface, and whiteface marked racial boundaries while reinforcing stereotypes in a consistently ‘readable’ vision of race for audiences, but An Octoroon intentionally subverts the melodramatic gaze by actively dismantling those visual markers of race at every turn. Jacobs-Jenkins forces his audiences to grapple with their complicity in the constructed nature of racial identity, both exposing the enduring legacies of racial representation on the American stage while offering a bold vision for theatre as a site of reckoning and deconstruction. Jacobs-Jenkins drives this message home by adapting the final moments of The Octoroon’s plot with a contemporary twist. In Boucicault’s version, Zoë’s tragic death – and her body’s symbolic ‘whitening’ in death – served as a critique of anti-miscegenation laws while appealing to white abolitionist sentiment. At the conclusion of the 2015 Theatre for a New Audience production, This act united performers and audience in a shared, unlit space, dissolving racial distinctions through the communal power of the human voice. The darkness subverted the audience of the privileged gaze that has historically separated and racialized bodies, offering them and the cast alike a fleeting moment of collective humanity. Cason Murphy is an Associate Professor of Theatre at Iowa State University, where he teaches courses in acting, script analysis, musical theatre, and performing arts studies. His research focuses on audience engagement, performance pedagogy, and the intersections of theatre, media, and popular culture as a site of cultural critique and performance innovation. He is the author of The World at Play: Performance from the Audience’s Perspective and has published in Theatre Journal, Theatre Topics, Shakespeare Bulletin, Theatre/Practice, Cinema Scandinavia, Journal of Film and Video, and The Thornton Wilder Journal, as well as in several edited collections. He holds his M.F.A. in Theatre Directing from Baylor University and a B.A. in Theatre Arts from UCLA.Back to top

Real and Imaginary Photography in The Octoroon and An Octoroon

Daniel A. Novak The photograph at the heart of Dion Boucicault’s Octoroon is at once an airy technological fantasy and an extremely real and material object both in the world of the play and on stage. In 1859, Scudder’s claim of to having invented a ‘self-developing liquid’41 that coats his photographic plates is so scientifically impossible as to be nonsensical. It was not until the development of the Polaroid in the 1940s that a version of this idea was realized.42 However, if, in anticipating the polaroid, Scudder’s photography is forward looking, it also harkens back to some of the earliest photographic technologies – the direct-positive technology of the daguerreotype and tintype. The negative/positive process we associate with modern photography co-existed with these direct-positive technologies; Henry Fox Talbot invented the calotype or talbotype a year after Daguerre introduced his process. But, the introduction of ‘wet-plate photography’ in 1851 – the coating of glass-plate negatives with light sensitive chemicals – allowed for the reproduction of prints from a single negative on a mass scale, and quickly became the dominant technology. Even if Scudder seems to nod to this when he refers to the ‘four plates’ he has ‘ready’ (p.38), the wet-plate process was much more laborious, requiring the photographer to coat each plate with chemicals right before inserting them into the camera. Pre-coated ‘dry plates’ weren’t available until 1871. Nevertheless, Scudder’s fantasy photographic technology works so flawlessly that it apparently can withstand Wahnotee smashing the camera ‘to pieces’ with a tomahawk (p.46). That is, this imaginary ‘self-developing’ photographic plate is so solid a reality as to be virtually indestructible. More important perhaps, this indestructibility is also intimately tied to photography’s role as divinely objective witness and unimpeachable proof of McClosky’s guilt: ‘[y]ou thought no witness saw the deed…but there was—the eye of the Eternal was on you—the blessed sun in heaven, that, looking down, struck upon this plate the image of the deed…’Tis true! the apparatus can’t lie. Look there, jurymen – (showing plate to the jury) – look there. Oh, you wanted evidence – you called for proof – Heaven has answered and convicted you’ (p.65). Just as the photographic technology is at once real and imaginary, here it is simultaneously a material and visible object and a manifestation of the divine and transcendent. This dual role is also central to the part that the photograph (and Scudder) play in the administration of justice. Both enforce an evidence-based and race-blind standard to counter the ‘Lynch law…a wild and lawless proceeding’ (p.65); both work to punish the murder of a Black slave (Paul) and protect a Native-American (Wahnotee) from being executed for a crime he didn’t commit in the Antebellum South. If Scudder’s Victorian polaroid is almost a hundred years too early, the play’s theory of the intersection of justice and race is arguably still unrealized. Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s An Octoroon reimagines Boucicault’s play in countless ways, so it is no surprise that it asks core questions about photography’s ontology and epistemology. At first glance, however, the words of the scene are largely unchanged from Boucicault’s, even if it is George who speaks these lines rather than Scudder. But, Jacobs-Jenkins interrupts the scene of photographic revelation; in the ensuing meta-theatrical dialogue, George breaks character and becomes an incredulous BJJ, who interrogates the character of the Playwright (Boucicault) about the strained theatrical logic of the device and the continued relevance of the photographic trope in the twenty-first century. While having someone ‘caught by a photograph’ would have been ‘novel’ in 1859, BJJ argues not only that ‘theatre is no longer a place of novelty,’ but that photography to us is both ‘boring’ and no longer credible as objective truth and evidence: ‘It’s a cliché, but we’ve gotten so used to photos and photographic images that we’ve basically learned how to fake them, so the kind of justice around which this whole thing hangs is actually a little dated.’43 For BJJ, the photograph is no longer what the nineteenth-century writer and photographer Lady Elizabeth Eastlake called ‘cheap, prompt, and correct facts…the sworn witness of everything presented to her view.’44 Without the photograph as proof, the race-blind justice ‘around which this whole thing hangs’ appears to be even more of an elusive fantasy. Like justice, the photograph itself is also elusive – literally impossible to grasp, as it is no longer a material object. Instead, using an ‘overhead projector’ (p.51), Scudder’s ‘photographic plate’ becomes a projection of a lynching photograph seen by the audience on the back wall of the theatre.45 (If BJJ felt that photography as a technology and as an epistemology was outdated and untrustworthy, even the projection is tied to the obsolete ‘overhead projector.’) Rather than being shown to the ‘jury’ on stage, the actors are blinded ‘in the light of the projection’ (51). Not only is the photograph no longer endowed with a divine, extra-theatrical authority and truth, it is also just as ephemeral as the performance on stage.46 Or rather, even more so, since the projector itself is shut off before George can repeat Scudder’s lines about the providential justice brought by ‘the eye of the Eternal’ that ‘struck upon this plate the image of the deed’ (p.51). Instead, George (as BJJ says) ‘I can’t see anything. I’m sorry—Can we turn this off? (The picture disappears)’ (51). As Peggy Phalen and others have argued, theatre and performance has long been associated with ephemerality: ‘Performance’s being . . . becomes itself through disappearance.’47 Photography, by contrast is usually theorized as a desire to freeze time and place in an objective, mechanically produced, reproducible, visible, and tangible image. An Octoroon challenges these fundamental assumptions about what a photograph is and what it does (and is capable of doing). Boucicault’s Scudder may have dreamed up a polaroid-like image in the mid-nineteenth century, but Jacobs-Jenkins reimagines the material photograph as an even more futuristic digital or virtual image – one that flickers between reality and imagination, visibility and disappearance, mechanical reproduction and theatrical performance. Daniel A. Novak is Associate Professor of English at the University of Alabama. He is author of Realism, Photography, and Nineteenth-Century Fiction (Cambridge University Press, 2008), and co-editor with James Catano of Masculinity Lessons: Rethinking Men’s and Women’s Studies (Johns Hopkins University Press, November 2011). He has published essays in Representations, Victorian Studies, Novel, Criticism, Nineteenth-Century Theatre and Film and other venues. His current book project is entitled Victoria’s ‘Accursed Race’: The Cagots and Racial Thinking in Nineteenth-Century England.Back to top

Critique of the Melodramatic Tableau in An Octoroon

Carolyn Williams In conversation with Aoife Monks in 2022, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins said that he is ‘interested in form’ above all.48 In that same conversation, he acknowledged the form of the tableau as ‘the jewel in the crown of nineteenth-century theatre,’ pointing out that the tableau provides ‘an experience of time stopping’ and lets ‘the audience catch up to themselves intellectually.’ Those summative and interpretive provocations of the tableau are not the only resources of the form, as Jacobs-Jenkins makes clear through his sustained critique of the melodramatic tableau in An Octoroon (2014), his brilliant meta-melodrama founded on Dion Boucicault’s The Octoroon (1859). In An Octoroon the form and functions of the tableau are brought to the fore through parody, while Jacobs-Jenkins also pursues a complex argument about its relations to photography. The lynching photograph projected in Act IV as the ‘Sensation Scene’ performs a hyperbolic remediation of the melodramatic tableau. After the climax of the slave auction and the Sensation Scene in Acts III and IV, Jacobs-Jenkins jettisons the curtain tableau altogether, replacing it in one case with darkness. At the end of Act I, after announcing his intention to buy and ‘own that octoroon,’ the villain M’Closkystands with his hand extended toward the house. Music. An attempt at a tableau. He holds the tableau for a while before Dido walks in with a washing bucket and some laundry.49Dido realizes that she has ‘walked in on something,’ and they speak together awkwardly. He finally exits, ‘frazzled.’ When M’Closky returns, he ‘strikes [Dido] violently,’ and denounces her in scathingly racist and sexist terms for having interrupted him previously (‘Don’t you ever fuckin’ sneak up on me like that again, you n***** bitch!’). Then Act I immediately concludes when he achieves ‘An actual tableau’. M’Closky’s villainous declaration that he will ‘own that octoroon’ had been interrupted – as if his statement and pose represented the sexual act that he does in fact intend. His response, at first awkward and ‘frazzled,’ turns angry and violent after his humiliation at being caught in the act, and it is clear that he returns to beat and denounce Dido for having interrupted his pleasure. This dramatic sequence implies that the successful formation of a tableau can be seen as testimony to the specific system of patriarchal domination (property ownership in persons) at issue in the play. The parodic point inheres in the interruption; the closure of tableau is prevented, as is M’Closky’s pleasure in posturing. Eventually, though, the successful tableau is achieved after his retaliatory discharge of violence, suggesting perhaps that the system remains intact despite interruption, parody, and critique. The end of Act II evinces even more skepticism about the tableau. Paul has posed before the camera, inadvertently forming a tableau (since to be photographed he must be still). In that sense, as Aoife Monks points out, early photography, with its demands for long exposures, always requires a tableau. While Paul is posing, M’Closky murders him so as to capture the mail bag, which contains a letter from the firm of Mason Brothers promising financial relief for the mortgaged Terrebonne plantation. Wahnotee, Paul’s Native American companion, returns to find that Paul is dead. He smashes the camera with his tomahawk because he thinks the strange machine has killed Paul, as if it were a gun. Then he performs the conventional tableau of grief over Paul’s body, while the stage directions express insecurity: ‘Maybe he starts to make a grave – sobbing and digging with his hands? I don’t know. In any case, there’s a TABLEAU’. This stage direction implies its critique by suggesting that the tableau is a pat and conventional gesture of old-fashioned stagecraft, one that perhaps imposes a sense of closure even when the dramatic moment is uncertain of its purpose. Jacobs-Jenkins has his own ideas about new things the tableau can do (as we shall soon see). But here, the stage directions seem to focus on the conventionality itself – and seem to rummage for ideas about ‘maybe disrupting that conventionality with novelty. In a later play text, the stage directions continue: ‘Br’er Rabbit may wander through [the tableau]. Or not.’ The multivalent figure of Br’er Rabbit is mysterious every time it appears in this play; invoking the familiar trickster from African-American folktale, in this plot he may simply “wander . . . or not”; for our purposes at this point, perhaps it is enough to say that the appearance of this figure heightens the uncertainty about how to stage the tableau of mourning. Act III is chiefly concerned with the auction. (With Zoe displayed on a table, the scene presents a tableau staged as if it were a play-within-the-play.) M’Closky buys Zoe for $25,000, as in Boucicault’s play. This Act ends with a successful tableau, but the stage direction is again full of ironic uncertainty, even sarcasm: ‘M’Closky jumps up on his chair, throws money in the air, and makes it rain – perhaps literally, perhaps figuratively. The theater is a space of infinite possibility. TABLEAU.’ The tone raises the question: is the theater really a space of infinite possibility? The subsequent meta-theatrical discussion in Act IV will debate that very point. At the beginning of Act IV, ‘BJJ and PLAYWRIGHT step forward from the tableau [the concluding tableau of Act III] and darkness falls.’ This is the turning-point of the play. By stepping out of the tableau, they leave behind the stagecraft of the nineteenth century. The ensuing pervasive darkness will substitute for a concluding tableau at the end of Act IV. A meta-theatrical – specifically meta-melodramatic – discussion occupies the first half of Act IV. In part this discussion is meant to provide a lesson in theatre history for the twenty-first century audience. BJJ and Playwright discuss the structure of classic melodrama, pointing out that the climax of the action occurs in Act III – the slave auction, ‘which you just saw,’ says Playwright – while the ‘Sensation Scene’ occurs in Act IV. BJJ diffidently calls the Sensation Scene ‘your best “theatre trick”, if you will,’ while Playwright explains that it is meant to ‘overwhelm your audience’s senses to the end of building the truest illusion of reality.’

You’re just supposed to make people think, for just a second, that what they’re seeing is real and dangerous and sort of novel. . . . You basically sort of give your audience the moral, then you overwhelm them with fake destruction.They then tell the audience what happens in the Boucicault play, emphasizing the improbability and randomness of some plot points and criticizing the play’s rattletrap construction and its over-the-top sentimentality in the courtroom scene. The famous photograph that appears in Boucicault’s play (as proof that M’Closky murdered Paul) comes in for a great deal of critique in An Octoroon: ‘randomly someone has brought on the camera that Wahnotee smashed’ and that had been forgotten until now. BJJ asserts: ‘This is actually a hole in Boucicault’s plot. Not mine’. Of course, it’s not really a hole in Boucicault’s plot but rather a typical example of Chekhov’s gun, creating suspense; audience members would have felt all along that the camera would return. The critique of melodrama here seems a little desperate or naive, and Jacobs-Jenkins’s play becomes purposefully chaotic at this juncture. Using the photograph as evidence, George accuses M’Closky of the murder. But the nineteenth-century scene is immediately broken as BJJ and Playwright return to debate the evidentiary value of a photograph in the twenty-first century. At the time of Boucicault’s play, the argument runs, a photograph was ‘a novel thing,’ but to us in the present, it is ‘boring’ and ‘a little dated’. Since we now know full well that a photograph can be faked, it can no longer give people ‘a sense of having really witnessed something’. BJJ and Playwright discuss what sort of ‘theatre trick’ could be used now. ‘The final frontier, awkwardly enough, is probably just an actual experience of finality,’ offers BJJ. ‘Like – death, basically?’ responds Playwright. They continue to brainstorm. Maybe they could set fire to the theatre, save everyone one by one, and continue the performance ‘out on the street,’ but then they would only be able to do the show once, and ‘Soho Rep. doesn’t need that’. Maybe they could sacrifice an animal onstage, ‘like in the good old days’ of ancient theatre. BJJ says he ‘tried to figure out the next best thing’. And the next best thing turns out to be a photograph, after all. At this point, the Assistant ‘projects a LYNCHING PHOTOGRAPH onto the back wall’. The stage directions uncertainly allow for the photograph to stay (or not) while the trial scene continues. The play-within-the-play resumes at the point of George’s ‘circle of hearts’ speech – so we’re now back in the original nineteenth-century melodrama – and it is at this point that the photograph from George’s camera is revealed to the characters in the courtroom, showing the true villain in the attitude of his crime. Branden Jacobs-Jenkins accomplishes a formal tour de force here. In the action of the play-within-the-play, a miniaturized version of the tableau – in form of a photograph that only the characters can see – replicates the scene of the murder with the villain ‘in the very attitude of [his] crime’. Though An Octoroon does not dwell on this formal mirroring, we should notice that the photograph in Boucicault’s play serves as a miniaturized version of the melodramatic tableau while a maximalized extra-diegetic photograph of a lynching fills the back wall for the twenty-first century audience to see: another tableau. This technical mise-en-abyme puns on the way projection technology projects us into the future, after the time of early photography, after the time of slavery, yet shocking us with trustworthy photographic evidence that racist terrorism continues. In melodrama, the backstage is, after all, the traditional site for the projection of vision and haunting. While the characters in the Boucicault play shout ‘Lynch him!’ (first referring to Wahnotee and then to M’Closky), the Thus, this hyper-sensationalized content, showing the historical after-effects of slavery in shocking and repellent form, is presented using nineteenth-century stage technology. And this is a brilliant solution to the production problems that BJJ and Playwright have been discussing, for it encompasses both artifice in the theatre and the reality out of the theatre ‘on the street’. It depicts a terrifying act of sacrificial scapegoating as in ancient theatre, but within a horrifying, modern remediation. It is too shocking, finally, to be seen as a mere ‘theatre trick,’ yet it does overwhelm the audience with a sense of the ‘real and dangerous’. Thus, as Branden Jacobs-Jenkins put it in his conversation with Monks, the play is ‘calling the photo on its bluff of realism,’ but it ups the ante while raising the question of how such sensational material should be handled – or if it can be handled. In the New York production at the Soho Rep. (2014), the photograph was projected in the backstage of a proscenium theatre, and therefore it operated formally as a traditional melodramatic tableau, as I have argued. But in London, the Orange Tree Theatre (2017) staged this scene in the round.50 The lynching photograph was projected on both sides of a white sheet falling from the roof of the theatre on an angle. The actors stood looking up at it on all sides. As Aoife Monks pointed out, ‘there was a form of tableau but not a front-facing one.’51 Therefore, during the projection of the lynching photograph, audience members were looking at it but also at each other. Monks raised this in conversation with Jacobs-Jenkins, emphasizing the powerful effect on the audience ‘because we were confronted with other audience members looking at the image as well as the image itself.’52 This format makes a new point, asking audience members not only how they are to respond to this overwhelming photographic evidence, but also asking them to hold each other accountable. We are all complicit in this horror. Carolyn Williams is Distinguished Professor and Kenneth Burke Chair in English at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. In addition to many essays on Victorian theater, poetry, and the novel, she is the author of Gilbert and Sullivan: Gender, Genre, Parody (2011) and the editor of the Cambridge Companion to English Melodrama (2018). Earlier books are Transfigured World: Walter Pater’s Aesthetic Historicism (1989) and the co-edited collection of essays (with Laurel Brake and Lesley Higgins), Walter Pater: Transparencies of Desire (2002). She is currently writing about Victorian melodrama and the realist novel, under the working title ‘Melodramatic Form.’

Back to top

Notes:

- Jacobs-Jenkins 2013 play Appropriate also considers the afterlives of artefacts of lynching. The play is set in an old plantation house in Arkansas where a white family gather to process their dead father’s effects and estate. The revelation of a lynching souvenir album is the catalyst for their reckoning with their dead father’s financial and moral legacy and their own conflicting desires to profit from it. Crucially, in the production I saw at Donmar Warehouse in 2019, the audience are not shown or able to see any of the photographs or trophies. Branden Jacobs-Jenkins Appropriate (London: Nick Hern Books, 2019). ↩

- Joseph Roach 1992 ‘Mardi Gras Indians and Others: Genealogies of American Performance.’ Theatre Journal, 44.4, 461-483, (p.478). ↩

- Dion Boucicault The Octoroon in Plays by Dion Boucicault edited by Peter Thomson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp.133-169 (p.163). ↩

- David Mayer, ‘Encountering Melodrama’, Cambridge Companion to Victorian and Edwardian Drama, edited by Kerry Powell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp.145-163, (p.158). Note that the tableaux and, in this period, the photograph are also both predicated on creating a composition or pose and then holding it. In the case of the photograph this is because of the length of time needed for the plate to be exposed and take the image. ↩

- See Daniel A. Novak for further consideration of the role of the photograph, reproducibility and Boucicault’s sources for this element of the plot. Daniel A. Novak 2020 ‘When Boucicault was ‘Boucicaulted’: The Octoroon, Race, Photography and Pre-Adaptation’, Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film, 47.2, pp.156-178. ↩

- Roland Barthes Camera Lucida. (London: Vintage, 2000), pp.79-80. ↩

- The emphasis here on experiential proof contrasts with the diligent and path-breaking work done by, for example, the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership project at UCL and the databases they have produced from scrutinising the records of the Slave Compensation Commission which they describe as providing ‘a more or less complete census of slave-ownership in the British Empire in 1833’. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/history/research/centre-study-legacies-british-slavery-cslbs/projects-and-partners/legacies-british-slave [accessed 4 June2024]. It also contrasts with the testimony given by formerly enslaved people in oral and published form. ↩

- Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, An Octoroon (London: Nick Hern Books, 2018), p.68. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 68-69. ↩

- James Allen, Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (Twin Palms Press, 2001), p.177 ↩

- Collector James Allen, author and curator of Without Sanctuary also has a website which reproduces lynching photographs, all the information he has been able to collect about them and testimony from survivors and witnesses https://withoutsanctuary.org/pics_27_text.html accessed 6.6.24 ↩

- Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery and Self-Making in Nineteenth- Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1997) p. 22 ↩

- Martin Meisel, Realizations: Narrative Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), p.45 ↩

- Jane Kathleen Curry, ‘Spectacle and Sensation in The Octoroon/An Octoroon,’ Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film 46, no. 1 (2019): p.47. ↩

- Dion Boucicault, The Octoroon; or, Life in Louisiana. A Play, in Four Acts (London: Thomas Hailes Lacy, n.d.), p.40. ↩

- Daniel A. Novak, ‘When Boucicault was “Boucicaulted”: The Octoroon, Race, Photography, and Pre-adaptation,’ Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film 47, no. 2 (2020): p.161. ↩

- Juliet John, Dickens’s Villains: Melodrama, Character, Popular Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p.31. ↩

- Brian Larkin, ‘Promising Forms: The Political Aesthetics of Infrastructure’, in The Promise of Infrastructure, eds., N. Anand, A. Gupta, and H. Appel (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), pp. 175-202. ↩

- John S. Seberger and Geoffrey C. Bowker, ‘Humanistic infrastructure studies: hyper-functionality and the experience of the absurd,’ Information, Communication & Society 24, no. 12 (2021): p.1714. ↩

- Ibid. p.1714. ↩

- Ibid. p.1713. ↩

- Ibid. p.1714. ↩

- Ibid. p.1717. ↩

- Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, ‘An Octoroon,’ in Appropriate/An Octoroon: Plays (New York: Theatre Communications Group, 2019), ebook. ↩

- Dale Cockrell, Demons of Disorder : Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), ix. ↩

- Ayanna Thompson, Blackface (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021), p.68. ↩

- Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, An Octoroon (New York: Dramatists Play Service, Inc., 2015), 15. Italics author’s own. ↩

- Jacobs-Jenkins, An Octoroon, p.19. Italics author’s own. ↩

- Marvin McAllister, Whiting Up: Whiteface Minstrels and Stage Europeans in African American Performance (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), p.113. ↩

- Jane Kathleen Curry, ‘Spectacle and Sensation in The Octoroon/An Octoroon’, Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film 46.1 (2019), p.39. ↩

- Daphne Brooks, Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), p.32. ↩

- Jacobs-Jenkins, An Octoroon, p.60. ↩

- Christie Evangelisto. ‘Finding Solace in Complication: An Interview with Branden Jacobs-Jenkins.’ Signature Stories 8 (Winter 2004), p.20. ↩

- Helen Shaw. ‘Branden Jacobs-Jenkins.’ Time Out New York (14 June 2010). Web. http://www.timeout.com/newyork/theater/branden-jacob-jenkins. ↩

- Eliza Bent. ‘”Feel that Thought:” Branden Jacobs-Jenkins Talks Appropriate and Octoroon,’ American Theatre Magazine (May/June 2014), p.44. ↩

- Daphne A. Brooks. Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910. Durham, NC: Duke University Press (2006). p.42. ↩

- Ibid, p.27. ↩

- Dion Boucicault. The Octoroon. Stratford, NH: Ayer Company Publishers (1977), p.16. ↩

- Patrick Healy. ‘”The Octoroon” Director Withdraws.’ The New York Times The New York Times (17 Jun 2010). Web. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/18/theater/18arts-THEOCTOROOND_BRF.html. ↩

- Lester Walton. ‘LaFayette Theatre: A Long Step Forward.’ New York Age (13 January 1916), p.6. ↩

- Dion Boucicault, The Octoroon (Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2014), p. 38. ↩

- Peter Buse, The Camera Does the Rest: How Polaroid Changed Photography (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), p. 11. Edward Land began work on the Polaroid system in late 1943. See Christopher Bonanos, Instant: The Story of Polaroid (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2012), p. 35. ↩

- Brandon Jacobs-Jenkins, An Octoroon (New York: Dramatists Play Service Inc. 2015), p.50. ↩

- Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, ‘Photography’, in Classic Essays on Photography, ed. by Alan Trachtenberg (New Haven, CT: Leete’s Island Books, 1980), pp.39-68, quote at p. 65. ↩

- The effect of the projection and the position of the viewer depends on how the play is staged. The London production at the Orange Tree was staged in the round so that the audiences watched it on both sides of a hanging screen – and watched each other watching. Thanks to Aoife Monks for this observation. ↩

- If the lynching photograph in An Octoroon is an ephemeral projection, the lynching photographs at the center of Jacobs-Jenkins 2013 play Appropriate are very much material, vulnerable, and even valuable objects. Before the bulk of them are destroyed by Franz in a gesture of individual, familial, and historical cleansing, they promise to save the family from financial ruin. In the end, however, it turns out that Cassidy swiped some for herself and gives a handful to Rhys. Unlike the plantation house itself, the photographs and history of American racial terrorism and white complicity survive. ↩

- Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (New York: Routledge, 1993), p. 146. ↩

- Zoom conversation between Aoife Monks and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, 9 September 2022. An event sponsored by the “Boucicault at 250” project. Unless otherwise noted, remarks made by Monks and Jacobs-Jenkins are quoted from this conversation. ↩

- I am following the Soho Rep. (New York) text of the play, though I will later have something to say about the London productions at the Orange Tree and the National Theatres. Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, An Octoroon (New York: On Stage Press, 2014). ↩

- The production was transferred in 2018 to the Dorfman in the National Theatre. ↩

- Email correspondence on 28 June, 2024. ↩

- See elsewhere in this issue of CTR the interview by Aoife Monks with the designer of this production. (The design was developed through the course of the rehearsals. She had an empty model box with only the scale replica of the theatre itself in it. They then filled it with objects and details as they progressed – so the photo staging emerged through the work of the company rather than the designer’s pre-conceptions.) ↩