Jolly Abraham in conversation with Aoife Monks

Jolly Abraham is an actor/teacher who trained at the University of the North Carolina School of the Arts. As a professional actor she spent 16 years in New York City performing extensively on Broadway and off-Broadway and regionally, leading productions in such large theatres as The Guthrie, La Jolla Playhouse, Dallas Theatre Center and The Shakespeare Theatre of DC. She was an Adjunct Professor at NYU Tish School of the Arts. Abraham moved to Ireland in 2019, and has since worked with Irish companies such as Dead Center, Once Off Productions, The Gate theatre and The Abbey theatre. Abraham played the Assistant, Pete and Paul in the Abbey Theatre’s 2022 production directed by Anthony Simpson Pike. Here, she reflects on her navigation of melodrama, racial stereotypes and the meanings of the blackface make-up that she wore in her roles.

Aoife Monks: When did you first come across the play? What were your first responses to it when you first read it?

Jolly Abraham: I came across An Octoroon first when I auditioned for the Abbey’s production of it. And I loved it. I just thought it was so provocative and it was funny as anything. I grew up in America with reruns of old TV shows like The Jeffersons, Sanford and Son, All in the Family, a lot of Norman Lear, who deals with a lot of racial stereotypes in a lot of his comedies, and The Little Rascals and Shirley Temple movies. So, I know the characters from An Octoroon both through satire and also as ‘legitimate’ entertainment. So, to me it was hilarious. The play was hilarious.

Afterwards, I read The Octoroon as research, to understand where Branden Jacobs-Jenkins was coming from, because I had no idea about the original play. I saw an interview with Branden Jacobs-Jenkins where he said that he loved it. He was in college, I think, when he read it, and I think it really moved him. To be perfectly honest, when I read the original, I thought it was going be this white man version of slavery, blah, blah, blah. And so, when I read it, I was actually really surprised by how, for a mid-nineteenth century play, how empathetic I think Boucicault was attempting to be, and how he confronted people with the dilemma of slavery and the Black experience in America. I was pleasantly surprised by his empathy and compassion for this state of affairs. And I thought that was so interesting as an Irishman too. And I wondered if maybe he was able to write that because as an Irishman he was coming from a place of being marginalized too? The play ain’t perfect – don’t get me wrong – he still has his biases like we all do, but that’s what I appreciated about it.

AM: He walks a peculiar line, doesn’t he? Like you say, he provokes genuine compassion for enslaved people, and at the same time, he reconfirms or even invents loads of racial stereotypes. There’s a real complexity there, which I guess is the point of the Branden Jacobs-Jenkins version.

You clearly do a lot of research as an actor. Could you talk a little bit about how you prepare for a role? Do you start preparing, for example, before rehearsal starts?

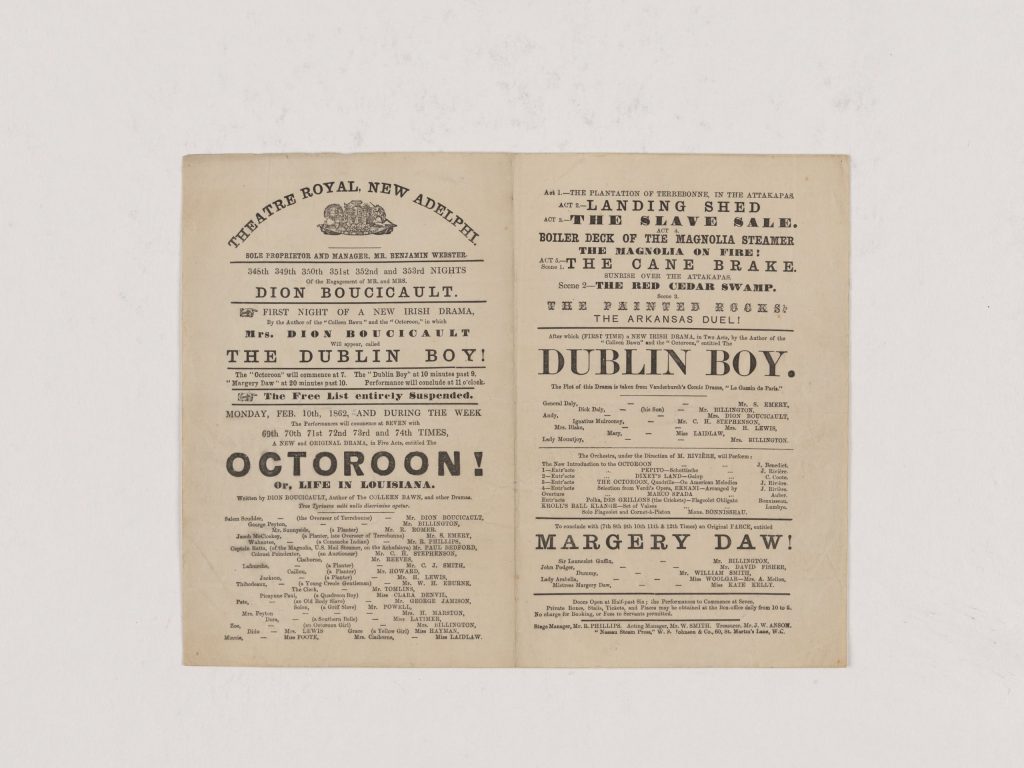

JA: With every play it’s a little different, depending on what the director wants to do. For An Octoroon, I looked at a lot of old movies and the old minstrel show posters. Our director Anthony Simpson Pike really wanted to explore the melodrama of this play. I think when you really go for the melodrama, really commit to it, it actually works better. If you do it too naturalistically you don’t really get the comedy of it, and the potential for satire. So I looked at a lot of the minstrel posters because I was thinking about using a lot of that as the physical language for Pete and Paul, the black characters in the play. I watched Little Rascals. I wanted to find the gross stereotypes to use onstage.

I also read a lot of Branden’s interviews from when the play first debuted, and also just about him as a writer, to find out what he’s interested in. I read a few of his other plays. I tend to try and read the other works by the same playwright because more often than not, there is a rhythm to their writing and there’s a style. So, reading all their work helps you find your way into the language and rhythm that’s in their head.

AM: I would imagine it’s reasonably rare for you to be cast as three characters in one show. You played the Assistant, Pete and Paul in this production, which of course is mandated by the script. Did you approach them as distinct roles? Did you understand them as intertwined? What was the relationship between the characters?

JA: I approached Pete and Paul as two distinct characters in the play. But with the Assistant you see her turn into Pete. So those lines are blurred. And then in the Third Act the play becomes presentational, and I tried to weave in Pete into the Assistant especially when the assistant says, ‘oh, there was a big explosion’ – I made a choice to end the line with a jazz-hands minstrel moment, which is not in the play. So, I brought Pete back in that moment. My wig was off, but I still had the black face on.

For the Assistant, during the Prologue when she puts on blackface, there was a moment when I made her look to the audience. I chose to look to the audience with apologetic eyes, like: ‘this is what I have to do, so excuse me. Because I’m about to do some things that are really absurd, funny, but also really offensive to some of you. I’m sorry.’

AM: What’s so interesting about that choice is the sense that people working at the theatre can be complicit with the harm it can do. And yet they also have limited choices because they are so precariously employed.

JA: Yes the approach I took to the Assistant was that she was like, ‘oh my God, I have to deal with this guy – Boucicault.’

AM: The Abbey production introduced a further element of crossing, by cross-gender casting your roles, and I wonder if that shaped your approach and your thinking? I notice you’re giving the Assistant a ‘she’ pronoun?

JA: To be honest I didn’t really think about it. We obviously got permission from Jacobs-Jenkins. In the character breakdowns, it states ‘an actor.’ It doesn’t say a female actor. It doesn’t say a male actor, it says an actor. So, Jacobs-Jenkins leaves it open to gender and he also leaves it open to several possible ethnicities. He doesn’t do that with the other characters. You know, he’s very specific about who’s allowed to play these certain characters, but with, you know, the Pete/Paul casting, it was Native American, Mixed Race or South Asian. I thought: ‘okay, well I fit into one of these brackets so I can do it.’

AM: Do you think it effected what Paul meant to the audience? Paul was played by a young white girl in blackface in the original Boucicault production, which connected with a Victorian tradition of women playing young characters we are supposed to feel sentimental about. Do you think that gender shaped the way Paul read for the audience in the Abbey? Or do you think they even registered it?

JA: I don’t know. I have no idea. That’s a really good point. That makes complete sense that a young woman would play the Paul role.

AM: How did you and the cast navigate the racial violence of the language in the original play, which of course, Jacobs-Jenkins reproduces? Was there a lot of conversation in rehearsal about what it means to say certain words in public?

JA: Yeah, we had a lot of conversations about words that we wanted to use in the room, and words we didn’t. I remember we didn’t say ‘slave’, we said ‘enslaved person’, which we were very particular about. We didn’t say the ‘N’ word unless we were doing the dialogue of the play. There were constant conversations about where we were all coming from, constant conversations about personal experience.

AM: What does it feel like to reproduce the physical vocabulary of minstrelsy?

JA: The creative team were all people of colour. Most of the cast were people of colour and along with our two Irish white actors, we were all just really compassionate, trustful human beings in the rehearsal room. That creates an environment where you can dive into the play. To me, that’s my job. It helps that the play is also really funny and well written. I’m not trying to make something work onstage – it already works. So there’s less of me having to figure out what to do.

Pete made people laugh all the time – playing him made the other actors, the other Black actresses on that stage with me – laugh all the time. And I think it is because I also am a woman of colour – it’s another person of colour who’s dealt with similar issues in her own personal life and we’re having fun.

But I looked my normal self in rehearsal. I didn’t actually put on the black face until we were in tech. Anthony warned everybody, and then I came out. All those people I had spent the last four weeks with having fun, laughing, joking – the way they looked at me was so different. It was like you could hear a pin drop: there was almost a collective inhalation. What I saw on their face made me tense up in my own heart and in my chest. And I thought, ‘how are we going to get past this moment?’ And we did eventually, you know, it took some time, we were able to get back to the play.

AM: Could I ask you a little more about the makeup?

JA: We used thick makeup because we were going to be sweating. That was the idea with Patrick who played M’Closkey and George: that eventually by the third act where we’re running around stage, we would started sweating off the makeup. We didn’t want to clean that up. But I also had discussions with Leonard the makeup artist about how we wanted the blackface to look. I wanted a version that was more of the stereotypes on the minstrel posters, which meant leaving the skin around the eyes clear of makeup, and then using the red stick paint to colour the lip and the area outside my lips. I felt if we went the route where all my face had been coloured in with the black paint it would recall photos of sorority girls going to Halloween parties in blackface and that didn’t seem quite right for our production.

AM: The play stipulates a really complex approach to casting for the roles that you played. The quote is that it must be played by a Native American actor, a Mixed-race actor, South Asian actor, or an actor who can pass as Native American. How did you feel when you got the role?

JA: It just gave me permission really. It gave me an explicit permission to do whatever the fuck I wanted in relation to this work, inside of the bounds of what I think Jacobs-Jenkins wanted, staying true to the essence of what this play is.

AM: The death of Paul is obviously a really important plot point in the play: it’s a moment where feelings happen for the audience. As you say, it’s a melodrama, so feelings are everything. Can you talk to me about how Paul’s death was staged in the Abbey production? How did you want the audience to feel at that moment?

JA: Paul is a naughty little mischievous boy, but he’s a sweet kid – that’s how I played him. He and the Native American character, Wahnotee, have a best buddy friendship, and I really wanted to make sure we created that strong relationship. When I read the play, I almost started tearing up when Paul dies but it wasn’t because Paul died, it was Wahnotee’s reaction to the death that made me cry. We staged the death as a comedic fall, where M’Closkey takes a hatchet and bumps me on the head and I just fell straight over.

But the point of the scene is Wahnotee’s reaction: it’s his wailing at the end of act one that pulled the audience out of this broad comedy. His keening over this child who he’s had this beautiful relationship with. I hoped that the audience would have grown to like Paul, this mischievous little rascal, by that point in the play. And this wail pushed the audience out of the comedy and told them: ‘wait, oh god, these are real people. These, these Black characters are real people.’

AM: Boucicault’s The Octoroon is sometimes seen as the first American play: it invents the idea of the frontier, the Wild West. Playing it in Ireland for an Irish audience of course means something really different. As an actor from the US, what was your sense was of what it meant to do the play in Ireland?

JA: For a while we weren’t sure how it was going to go over. My background is American, so I knew the absurdity of the play’s cultural references and I understood the complicity in American culture with those stereotypes too. I wasn’t sure if Irish audiences would even get a lot of the references, to be perfectly honest.

I remember our first preview audiences were medium sized but by the end of the run, they were full houses. I think there might have been a generational difference. The older audiences tend to come first because they’re Abbey people and I think they weren’t quite sure what to think of it. I don’t think they thought it was bad, but I think they just didn’t know how to make sense of it. I think in theatre you have to feel you have permission to laugh. And I don’t know if Irish audiences knew they could laugh at these terrible things that were being said on stage, the use of N-word, and just the terrible things we were saying to each other. But I think a younger Irish generation did know they could laugh. It might have also possibly been word of mouth got out about what the play was so that they came in with a different point of view. So, yeah, I think by the end people kind of got it.

I think Jacobs-Jenkins just has really interesting things to say about the American landscape that we live in today with echoes from the past and maybe into the future. And Boucicault is still affecting great playwrights today and audiences today. What a legacy.

Aoife Monks is Professor of Cultural and Creative Industries and Director of the Centre for Creative Collaboration at Queen Mary University of London. Her research focuses on costume and backstage work at the theatre, as well as engaging with histories of virtuosity, entrepreneurialism and Irishness during the Celtic Tiger economy in Ireland. She is the PI (with Nicholas Daly) of the AHRC funded research network Boucicault 2020: Circuits of Skill – which this special issue is one outcome.